How Basketball is Being Gentrified from the Top Down

Walk into a youth basketball tournament today, and you might think you’re at a corporate expo. Team banners sponsored by shoe companies. Uniforms with customized branding. Private trainers are pacing the sidelines—$ 30 entry fees for parents to watch.

This isn’t the game many of us grew up with.

This is basketball — gentrified.

In cities across America, from high school gyms to elite prep schools, the sport is undergoing a quiet but profound transformation. Just like urban gentrification, it’s displacing the people who built the culture.

Welcome to the new game.

From Streetball to Pay-to-Play

Basketball has always been a sport of access. A ball, a hoop, and a dream were all you needed. For generations, Black communities, especially, have turned courts into proving grounds.

However, over the last 20 years, youth basketball has evolved into a multi-billion-dollar industry. Elite travel teams, recruiting services, and exposure camps now form a pay-to-play pipeline to college scholarships. If you can’t afford the ride, you’re left at the curb.

According to the Aspen Institute’s State of Play report, the average family spends more than $1,100 each year per child on basketball. This amount does not include major circuits like Nike EYBL, Adidas 3SSB, or Under Armour’s UAA. When you add in expenses for private trainers, shooting machines, and out-of-state tournaments, the costs can increase significantly.

Low-income families — disproportionately Black and Brown — are priced out of opportunity. The players who do break through? Their stories are still marketed like Fairy tales.

The Stewards Are Not the Creators

The commercialization of basketball has created a clear divide between those who create value in the sport and those who capture it.

Black athletes dominate the courts at every level, from youth to NCAA and NBA. But when it comes to ownership, infrastructure, and decision-making? The numbers drop off a cliff.

Only one majority Black owner exists in the NBA: Michael Jordan (and he sold his controlling stake in 2023). At the collegiate level, most athletic directors, conference commissioners, and university boosters making decisions about sports are white. It’s not just underrepresentation — it’s exclusion.

As Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) opportunities expand in high schools and colleges, new chances are arising for athletes. However, the resources that facilitate this empowerment—such as legal guidance, brand strategy, and financial literacy—are still mainly found within elite networks, which are often distant from the average public school or community gym.

Once again, opportunity is framed as universal, while access remains selective.

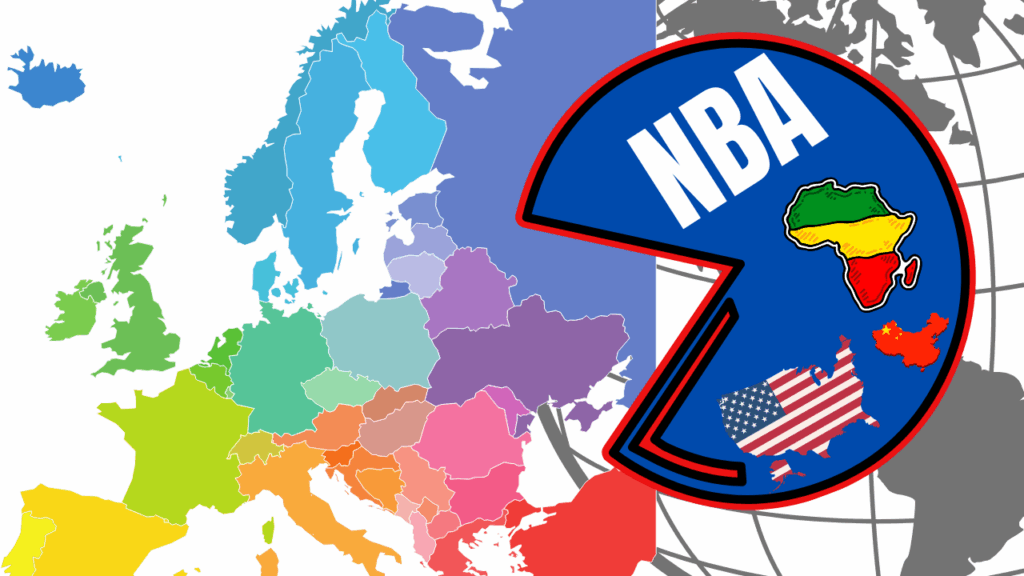

Basketball’s Global Rebrand

Here’s the twist: while the U.S. youth basketball system becomes harder to navigate, NCAA programs are looking overseas to fill rosters.

Between 2012 and 2023, the number of international players in Division I men’s basketball increased by over 45%. The reason for this rise is straightforward: economics. International players often receive better development, tend to be older due to their participation in academy systems, and do not face the complications associated with America’s flawed amateur pipeline.

It’s not a conspiracy — it’s a business decision. But it adds pressure to already vulnerable American players. Fewer spots. More politics. The message? You must adapt quickly or you will be replaced.

For American-African athletes in particular, this shift represents a new form of displacement. They are still the heartbeat of the sport — the cultural capital — but not the strategic priority.

Up Next in the Series:

“Displaced at the Rim: How Black American Communities Are Being Pushed Out of the Game They Built”

Mark Tee Armstrong promotes an alternative, no-backboard sport as a solution to both access and ownership in American basketball. You can learn more about the No Backboard Basketball League here.